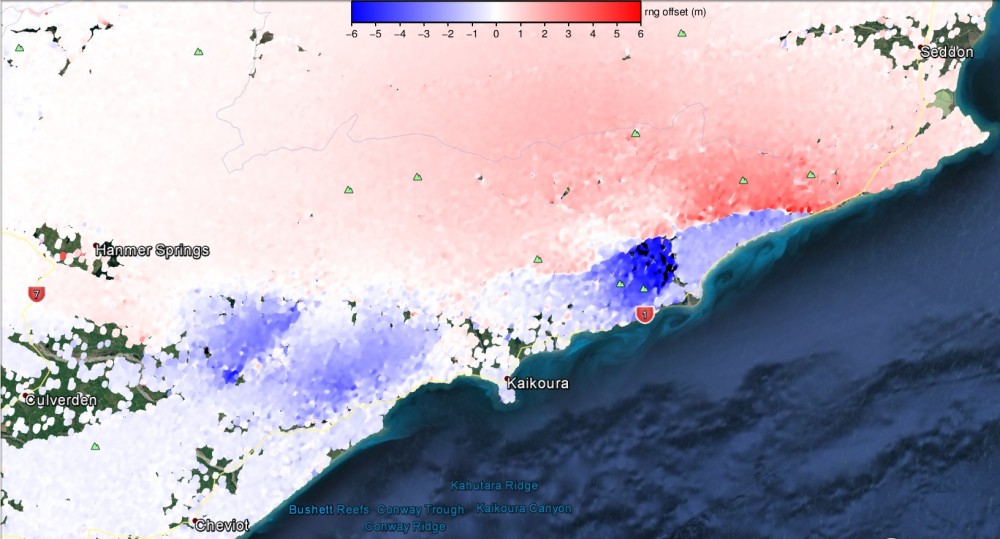

Working with collaborators at GNS New Zealand (Ian Hamling and colleagues), we have been examining the major Kaikoura earthquake from November 2016 which shook the South Island. By using the latest satellite instruments and data, combined with field observations, we were able to constrain the complexity of this multi-fault rupture and determine the magnitude of uplift of different fault blocks. This study was recently published in the journal Science, with news coverage provided in the BBC.

Earthquakes involve rupture of faults within the crust. Earthquakes which are big tend to rupture large faults. The segmentation of faults refers to how these faults are broken up into bits, normally 10 to 50 km long. The further faults are apart, the less likely they are to break together in a single earthquake. However, this particular New Zealand earthquake involved 12 different fault segments snapping in quick succession over the course of a minute or two, some spaced relatively far apart. Constraining this large degree of complexity is important for revisiting the way seismic hazard models are run. A reevaluation is required in these hazard assessments to allow for earthquake scenarios that involve a wider network of faults to take part in a given earthquake.

As well as the seismic hazard, these types of earthquake provide important insights into how large mountain ranges such as those seen on the South Island of New Zealand, are formed. The satellite data revealed large pop up structures as crustal scale blocks 10 km wide moved vertically by over 10 metres in this one event. These large displacements which are repeated to a lesser extent further south, seem to point towards an important way of rapidly building topography, uplifting the coastline to form mountains.